Mayfield

Key Sustainability Objectives/outcomes and Approaches Used

The development at Mayfield Park represents a change in the way landscape-led approaches are applied to city-centre developments and can demonstrate smarter, more effective, climate resilient design that builds in Nature-based Solutions from the outset.

The project makes the case to consider alternatives to avoid harder engineered options, by creating a 6.5-acre park with 80% of the materials from site being reused effectively and sustainably.

Green open space is one of our best tools in fighting the climate and biodiversity emergencies in urban areas. The Mayfield Partnership has delivered a park, naturalised a river channel, including “daylighting” of a heavily culverted section, and delivered a mosaic of natural habitats along its length.

The park will act as a flood zone for the River Medlock during extreme weather events, to help minimise flood risk elsewhere in Manchester.

By planting 63,000 plants, 60,000 bulbs and 140 trees (40 different species), the park will improve air quality by reducing nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter. Additionally, these plants will reduce air temperatures and, when coupled with the river, they will provide a respite for city residents during our warmer summers.

The Park will also offer climate-resilient habitats for flora and fauna to thrive, creating space that includes a 1.5-acre wildscape area to support an urban ecosystem. Geomorphological modelling of the river has identified opportunities for fluvial and riparian habitats that have been incorporated into the design, as well as 26 different habitat features on land.

Close working relationships between the landscape architect, the project ecologist, the hydrological consultant, and interested bodies including Greater Manchester Ecology Unit and the Environment Agency meant that habitat design was achievable, proportionate, and realistic for an urban park in central Manchester. This led to biodiversity net gain calculations, undertaken using Natural England’s Biodiversity Metric 2.0, to produce approximately a 90% net gain for biodiversity for Phase 1 of the development, provided by the park alone. As the project continues to develop the built plots around the park, further additions to the net gain will be made as development plots continue the greening of the Mayfield area.

The flora of the park is specified to be resilient to the local climate. If irrigation is required, three existing wells have been reactivated and will provide water for the park, eliminating irrigation demand on city-wide water networks. This intervention will save an estimated 3 million litres of water and one tonne of carbon a year.

Lessons Learnt

During the detailed design stages, the value engineering assessment identified that a more proportionate and sustainable approach to the redevelopment of the land on site into a park would be to reduce the amount of regrading of the existing site levels. This would reduce the requirement to rebuild retaining walls elsewhere on site to support stability of future built plots while also reducing the amount of remediation required to treat unearthed contaminated ground.

As a result, more existing walls were retained around the river corridor, reducing the available area of riparian habitat that could be created and the subsequent value of post-development habitats. Additionally, the development of detailed planting palettes also meant that some habitats included at the outline stage would not be created based on the species chosen in the planting, and so some areas of the designed park reduced in value due to a change in assigned habitats based on the produced species list. This was partly led by the regrading exercise as the appropriateness of some planting types changed due to the changes in proposed site topography.

This illustrates how targets for habitat and planting types need to be proportionate, realistic, and achievable at the outline stage when the supporting details behind them are likely to be lacking. Whilst a reduction in the net gain delivered was incurred, the park still achieved over a 90% gain on the baseline level.

Related

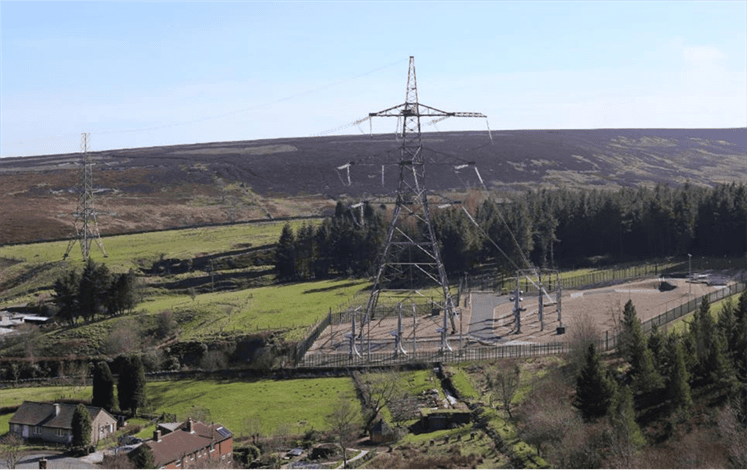

Visual Impact Provision (VIP) – Peak District East

Brighouse Flood Alleviation Scheme

Duxford Old River Floodplain Restoration Project & Habitat Bank

Halifax Bus Station