Embodied Ecological Impacts

We are in the middle of a global biodiversity crisis, with a 69% decline in global biodiversity populations since 1970. Biodiversity is increasingly being considered within the built environment, alongside the recognised need for green and healthy urban environments. However, worldwide only 1% of our planet’s surface area is used for buildings and infrastructure, so focusing on the site level alone will not be enough to tackle our global nature and biodiversity crisis.

The impacts of the construction industry reach beyond the footprints of our towns and cities and they extend well beyond country borders. In a world of globalised trade and supply chains, many negative impacts are transferred to sites and areas remote from the building site, such as deforestation, water scarcity, pollution, and even violent conflicts. These can be hard to identify in a fragmented, global industry that often lacks transparency.

We need to consider the full picture of the way we impact nature via the ways we do business. This includes ecological impacts as a result of material extraction and within our supply chains. This is what we call embodied ecological impacts.

Latest Updates

In November 2024, we threw our first Embodied Ecological Impacts Conference, where over 100 attendees joined together to share learnings, expand their networks, and discuss how to integrate EEI in their projects. Read our blog by Kai Liebetanz, our Head of Nature, to learn more about the critical insights that emerged from the conference.

Materials Map

About the Global Map

This map shows the main locations for material extraction where applicable, overlayed with biodiversity hotspots. This refers to global material extraction, independent of where the UK imports its resources from. Highlighted countries of extraction account for at least 50% for global supply of that resource.

Each material as well as the biodiversity hotspots can be toggled on and off via the Filter button in the top right. Clicking on Learn more within the Filter section opens a page with more UK-specific in-depth information for each material, covering methods of extraction, key ecological impacts, as well as recommendations and links to further resources.

Data is based on: US Geological Society (Iron, Aluminium)Luckeneder (2021) (Iron, Aluminium), Food and Agriculture organization of the UN (Timber), Mineral Products Association (Aggregates, Cement), Office for National Statistics (Aggregates, Cement), British Geological Survey (Aggregates, Cement)

Materials in this map

Aggregates

Aluminium

Cement

Iron Ore

Timber

Context

What do we mean by Embodied Ecological Impacts?

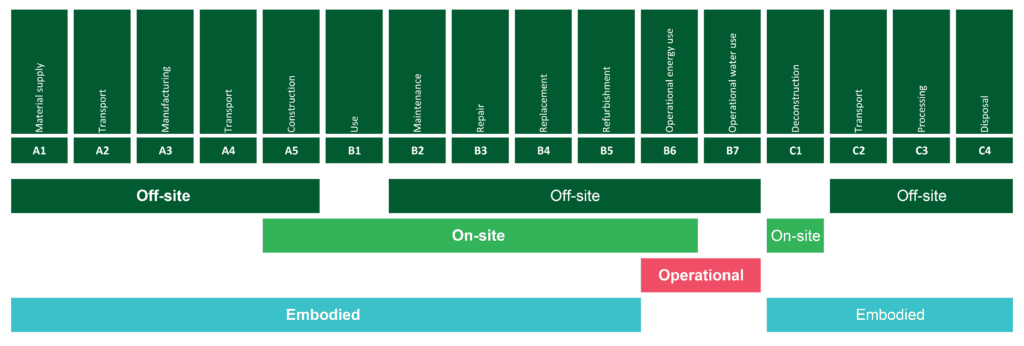

Similar to embodied carbon, embodied ecological impacts are caused by the resource extraction and manufacturing process, such as the production and transportation of raw materials and the disposal of unused materials. These impacts occur offsite, mainly via materials extraction and the supply chain. Local, on-site impacts of the built environment on biodiversity are not included in this definition.

Ecological impacts refer to the effects of human activities on the natural environment, ecosystems, and biodiversity. These impacts can be both positive and negative, and they may be direct or indirect, depending on where you sit in the supply chain. The work presented here focuses mainly on negative and indirect ecological impacts.

Embodied Ecological Impacts and Carbon

The concept of embodied impacts is already well-established for carbon. As demonstrated above, we can address ecological impacts in a similar way, using a whole-life framework.

However, there are several key differences. Carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases are assessed using emissions of greenhouse gas emissions including carbon, whereas ecological impacts are more varied and complex to capture. Unlike carbon, which has the same impact globally, wherever it is released, ecological impacts are often specific to local environments, interconnected with other ecosystems, and therefore impossible to address universally.

UKGBC’s work on embodied ecological impacts

UKGBC’s work on embodied ecological impacts aims to:

- Raise awareness of global ecological impacts

- Put nature loss firmly on the agenda for the built environment

- Advocate for a holistic view of nature among built environment practitioners

We focus on the ecological impacts of our supply chain, especially on common raw materials linked to the built environment. Our aim is to identify hot spots of ecological impacts in our supply chain as well as geographically.

This page is intended to be dynamic, with content being added as the conversation progresses. Please get in touch with us if you have information to contribute or think anything should be added.

The problem

The destruction of our natural environment continues to make headlines, largely driven by changes in how we use land and extract resources. If everyone lived like a resident of the UK, we would require the resource equivalent of 2.6 Earths, which is a model we can’t sustain. Our total material extraction has doubled since 2000. Given the constraints of finite resources, it’s imperative that we alter our approach to material consumption, reconsider the consequences of extraction, and ensure equitable global access to these resources.

Currently, resource extraction is expected to increase. According to the OECD, many construction-related materials are forecast to double by 2060 under the business-as-usual scenario. Still, we continue to treat our resources as endless and keep extracting, using, and wasting them through a linear economy. Since absolute decoupling of ecological impacts from resource extraction is impossible, alternative ways of managing and distributing finite resources need to be explored.

The built environment is the most resource-intense sector, whilst also providing many positive societal outcomes such as shelter, and social cohesion. Finding better ways to collectively decide how and where we prioritise resource use to ensure a good standard of living for all is key.

For this, we need to shift from having predominantly negative ecological impacts towards cultivating positive impacts and relationships with nature and ecosystems. Staying within our planetary boundaries and shifting towards a circular economy will be fundamental to achieving this.

Understanding the problem

International Context

Living in harmony with nature

“By 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people.”

- Ecosystem and species conservation, restoration, integrity, connectivity

- Sustainable use of resources

- Equitable sharing of benefits

- Means of implementation including alignment of financial flows

23 targets for urgent action over the decade to 2030

> Reducing threats to biodiversity

> Meeting people’s needs

> Tools and solutions for implementation

Business Context

Like the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) seeks to enable companies and financial institutions to better understand and disclose the potential impact of environmental issues on their business operations, value chains, and financial performance. However, the TNFD focuses specifically on nature-related risks and opportunities, including biodiversity loss, deforestation, pollution, and the sustainability of natural resources.

Similar to the Science-Based Targets initiative for carbon emissions reduction (SBTi), the SBTN initiative provides a framework for companies to develop meaningful and measurable targets for their impacts on nature. It allows companies to align their operations and activities with science-based practices that are essential for maintaining and restoring biodiversity and ecosystems. By setting science-based targets for nature, companies can contribute to the overall goal of halting the alarming decline in biodiversity and preserving the health and resilience of ecosystems worldwide

How does the built environment affect nature?

Energy Transition

Construction

Infrastructure

Fit-out

We need to move away from destructive and extractive practices in the built environment, building upon emerging concepts such as being nature-positive and regenerative. Crucially, we need to form a deeper understanding as an industry of what this means in practice. Assessing our impacts on nature and biodiversity holistically means getting familiar with the concept of embodied ecological impacts.

Definitions

Being nature-positive in line with the Global Goal for Nature is defined as halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030 compared to a baseline of 2020.

More specifically, it centres around three time-bound goals: zero net loss of nature from 2020, net positive by 2030, and full recovery by 2050. The Nature Positive Initiative is currently driving alignment around the use of the term and is developing measurable outcomes to achieve its goals.

From a business perspective, nature-positive is not yet well defined.

As a global goal, nature-positivity provides a direction of travel. Currently, claiming to be regenerative as a business, or attributing this term to built assets, cannot be sufficiently backed up in all its complexity. Being nature-positive should therefore act as a guiding vision, rather than certification.

Being regenerative is about enabling social and ecological systems to maintain and improve their own health. This needs holistic systemic thinking and practices, with the goal of enabling natural and human systems to repair, thrive, adapt, and co-evolve.

Currently, claiming to be regenerative as a business, or attributing this term to built assets, cannot be sufficiently evidenced due to the complex interconnectedness of ecosystems and global supply chains. Being regenerative should therefore act as a guiding vision, rather than certification.

Overall recommendations

Apart from the assessments of individual materials, there are several overarching recommendations, both on an organisational level as well as on a project level. These are a good starting point for a more holistic approach to nature and biodiversity for stakeholders in the built environment.

Project Level

Use the resource use mitigation hierarchy to prioritise actions to drive down embodied ecological impacts.

Embrace the circular economy

Engage with your supply chain

The Mitigation Hierarchy

Prioritise best use of existing assets.

Prioritise reused materials and match availability.

Prioritise recycled and biobased materials and match availability.

Optimise design.

Regenerative or low-impact material extraction.

Avoid Material

Organisational Level

Embrace existing and emerging frameworks.

Perform a materiality screening and value chain assessment

Set an organisational nature and biodiversity strategy.

Discover the Impact

Materials included in this study

We have identified 5 raw materials to be analysed in greater detail below, including methods of extraction, key ecological impacts as well as solutions to the issues we are facing. These are commonly used raw materials in our industry and more materials will be added over time to build up a more complete picture.

The provenance and impact of materials need to be evaluated based on where materials are extracted globally, and where the UK imports raw materials from. The following analysis will focus on the UK’s impact via materials, both inside and outside the country, based on the main locations that materials used in the UK are extracted from. However, one country’s impact is not independent from others, as resource limits are global and need to be addressed as such. A shift towards widespread adoption of the principles included in the resource use mitigation hierarchy must therefore be a priority.

As a hub for information on ecological impacts, we intend to keep this page dynamic and collaborative, adding information over time, as well as different materials. If you want to share information or case studies with us, you will be able to do so using the buttons in the materials section, or at the end of this page.

Impact Rating

Material extraction for construction comes with various ecological impacts. Currently, quantifying the full extent these impacts is challenging due to data availability and scarcity of open disclosures. To align with SBTN guidance, this assessment adopts the impact categories biodiversity, climate, land, freshwater, and ocean. Additionally, a category indicating impacts on human wellbeing has been added to complete the picture.

The impact score for each impact category can range from zero (indicating no impact) to four (reflecting a very high impact). This score is influenced by the extraction methods and geographic source of the materials imported for use in the UK, as well as those produced within the UK. Therefore, the negative impact score associated with each material can be considered as a high-level approximation to the construction industry in the UK.

Further Resources

WWF Risk Filter

A global location-based screening tool to identify biodiversity and water risks and prioritise corporate action on biodiversity.

Encore Tool

A free tool for assessing impacts and dependencies on nature for different sectors

Environmental Justice Atlas

A global database of socio-environmental conflicts specific to locations worldwide.

The Embodied Biodiversity Impacts of Construction Materials

The report takes a first step to enabling those working in the built environment to understand how biodiversity is impacted throughout the lifecycles of five common construction materials.

Science Based Targets for Nature

Setting science-based targets for nature: a step-by-step guide

The Taskforce for nature-related financial disclosure

Developing and delivering a risk management and disclosure framework for organisations to report and act on evolving nature-related risks.

OEC Database

A database to explore trade data of materials.

IStructE short guides

Short guides to carbon factors for key materials.

Acknowledgments

Resilience & Nature Programme Partners

With thanks to our programme partners who make our work on nature possible.

Project partners

With thanks to the following partners for making our Embodied Ecological Impacts work possible

Task Group

AtkinsRéalis – Kelly Gunnell

Berkeley Group – Jessica Lewis

Biodiversify – Mike Burgass

BNP Paribas Real Estate – Donna Rourke

Buro Happold – Alexandra Jonca

Firstplanit – Ankita Dwivedi

Greengage – Chris Moss

Hilson Moran – Thomas Hall

JLL – Amanda Skeldon

Nature metrics – Pippa Howard

Pollination Group – Gemma Cranston

Ramboll – Samantha Deacon

TfT – Rachel Cakebread

The Carbon Trust – Tianqi Li

UKGBC team

Project Lead – Kai Liebetanz

Authors – Kai Liebetanz, Clare Wilde, Macarena Cárdenas

Editor – Smith Mordak