How the urban heat island effect makes cities vulnerable to climate change

Climate change is global. But the impacts are experienced locally, on individual people and the assets they own and use on a daily basis. Increasingly, cities are experiencing the consequences of climate change. In the summer of 2022 UK heatwave exceeded extreme temperatures of 40℃ for the first time leading to wildfires in London and energy use and prices soaring. By 2030, it is estimated that 1.9 billion people will be exposed to heat stress, especially those in cities.

What is an urban heat island?

Temperatures can vary significantly even across a relatively small area. Densely populated city areas can be up to 12°C warmer than the surrounding countryside. This localized warming within cities is known as the urban heat island effect.

Cities are covered with human-made materials such as roads and buildings which absorb and retain heat better than natural surfaces like grass or woodland. Albedo describes how reflective a surface is. High albedo surfaces, such as white roofs, are reflective and absorb less heat than low albedo surfaces such as asphalt roads. Vegetation cools the air around it through the evaporation of water. Vegetation cover and albedo are two of the most important factors which determine the strength of the urban heat island effect.

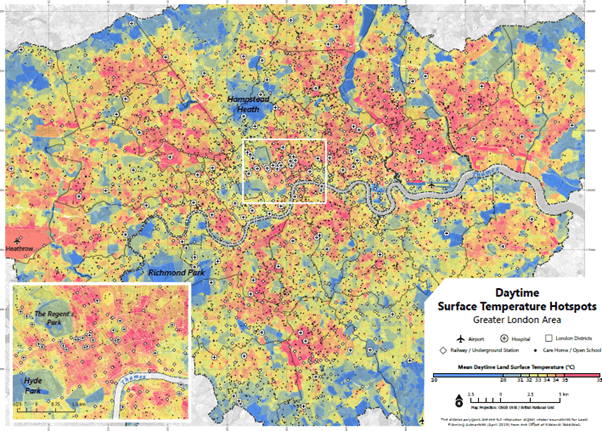

Satellite thermal data published by the Greater London Authority shows the albedo effect in action. This map visualizes London’s daytime surface temperature, showing cooler daytime temperatures in green areas with lots of vegetation, such as Hampstead Heath, in contrast with hotspots such as Heathrow which are paved with asphalt.

What does extreme heat do to the human body?

The world is experiencing hotter days, more frequently and for longer consecutive periods of time. However, heat is not the only factor that determines the impact of a heatwave.

People who work outdoors, like the 3.1 million people employed by the construction sector, will literally need to down tools and stop because of the heat

Humidity is a measure of how much water vapor is present in the air, and warmer air holds more water. Climate change is shifting humidity patterns, making some areas more humid, and some less humid. At 100% relative humidity (also known as wet-bulb temperature), the air is fully saturated with water, so sweat won’t evaporate. The body cannot regulate its temperature to cool itself down. At a wet-bulb temperature of 35°C, people won’t survive for more than a few hours even with shade or water.

Managing a farm in Ghana, Cervest’s Founder and CEO, Iggy Bassi, witnessed severely hot conditions first-hand, “On extreme heat days, we knew ahead of time we had to change all of our labor rotas,” he says. “Beyond a certain temperature, the human body cannot work because the outside humidity is so high.”

People who work outdoors, like the 3.1 million people employed by the construction sector, will literally need to down tools and stop because of the heat, increasing the cost of operational downtime. In extreme circumstances, without access to cooling, working conditions become inhumane and life-threatening.

The impact of heat stress on employee health has been linked to lower productivity and increased absenteeism and has big financial implications for businesses. To avoid negative impacts on employee health, employers will need to absorb costs from changing energy requirements and adapting buildings to cope with increased heat.

How does extreme heat affect buildings and critical infrastructure?

Extreme heat impacts more than health and productivity, it can structurally damage buildings roads and infrastructure. Heat causes building materials expand and metal to rust faster. This has big implications for concrete structures, especially those internally reinforced with steel. Half the world’s buildings are constructed with concrete, housing 70% of the world’s population. Another structural problem caused by heat is soil shrinkage, making building foundations more vulnerable to subsidence. The British Geological Society (BGS) highlights this as an escalating problem in northern and central London boroughs, and in Kent in the South East due to climate change.

Simply put, UK cities weren’t built with the consequences of the urban island effect in mind. Compared to other hot countries, UK buildings were designed to keep heat in and rarely have air conditioning. With heatwave-induced GDP losses in Europe expected to surpass 1.14% in 2060, the cost of inaction is heating up.

UKGBC’s Climate Resilience Roadmap

Building on the experience of UKGBC’s groundbreaking Whole Life Carbon Roadmap launched at COP26 in Glasgow, the UK Climate Resilience Roadmap will be a collaborative effort between some of the built environment’s most influential, trusted, and experienced players using cutting-edge insights at the forefront of global industry.

This Roadmap will have a wide remit, encompassing all of the UK built environment from the busiest metropolis to a rural community. The project will take a holistic view as it examines infrastructure, buildings and systems, and grapples with a number of climatic hazards – including overheating. Ultimately, industry members will have a clear path to follow to ensure that UK communities are resilient, safe and prosperous as the temperatures increase.

Related

Introducing the UK Climate Resilience Roadmap

Unveiling the Climate Risks: Voices from UK’s Built Environment

What learnings can we take from the UK Climate Resilience Programme?

What is it like to measure the physical risk of built assets?